A few days after entering the war, the Italian Air Force Command – under specific request of the Army’s staff – began to work out a plan to establish a regular link system between Italy and Eastern Africa. The unfavourable geo-political configuration of the African territories (Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia) belonging to the Italian empire and the huge distance between the latter and both the motherland and Libya, forced the headquarters of Army, Navy and Air Forces to find out a remedy to one of the most serious and immediately negative consequences coming out from the Italian declaration of war of June 10, 1940.

The state of belligerency with Great Britain and France had caused the prompt isolation of all the Italian East African dominions which – being bounded by Sudan on the north and the west, by Kenya on the south, by British and French Somalia on the west – turned out to be completely surrounded by the enemy. In addition, both the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean were patrolled by the powerful Royal Navy. Considering the situation, there was nothing left to the Italian high command but think up one (or more) emergency plan to try to supply the war forces under the command of viceroy Duke Amedeo of Aosta. On this regard, it is important to point out that as from October 1939 – i.e. long before the Italian entering in the war – the Duke himself (and before him his predecessor, Marshal Rodolfo Graziani) had reported to Marshal Pietro Badoglio and to Mussolini that, in case of conflict, the provisions of fuel, lubricant oils, spare parts, tires and ammunitions stocked in the African warehouses should have run out in a few months(1).

The Duke’s concerns were proportioned to the actual state-of-facts, but they had never seriously been considered by Badoglio and Mussolini, who figured out the Italian participation to war as something like a few-weeks trip. This wrong conviction was even strengthened at the beginning of June 1940 in the mind of Mussolini and his high counsellors (such as that champion of opportunism who was his son-in-law, the Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano) by the overwhelming victories got by the Wehrmacht in Poland, Denmark, Norway, Holland and France. On the days after the declaration of war – and due to the geo-political reasons mentioned before – the big shots of Rome realised that it would not be possible to send large supplies by sea to Italian East Africa (IEA); even if a clumsy attempt was carried out thanks to the co-operation of Japan(2). To supply by air was therefore the only chance which, obviously, could fulfil the real needs only in a small quantity.

At that time, the Regia Aviazione’s cargo aircrafts able to perform such long distance voyages were of course not comparable in fuel range and cargo capacity to the present ones. Moreover, they were very few. In June 1940, Italy had a few tens of three-engine cargo aircrafts which could cover – without any intermediate stop – the distances between the Libyan airports (in which they had anyway to stop) and the Ethiopian or Eritrean runways. The only cargoes to have enough range were the Savoia Marchetti SM83, SM75 and SM82, most of which belonging to the national air company Ala Littoria (excluding a few SM82, already registered in the military aviation and a couple of SM79 fighters, converted in emergency cargoes).

The debut of the Transatlantic SM83.

The first Italian aircraft to have the honour and the burden to start – at war already outbroken – the series of links between Italy and IEA, was a Savoia Marchetti SM83, namely the SM83 615-1 belonging to the 615th Squadron of Nucleo Comunicazioni LATI (Italian Transcontinental Air Lines Communication Team). The plane was a compact and strong three-engine machine, designed in 1937 by Alessandro Marchetti to accomplish the task of long range cargo and passenger aircraft. Its good technical characteristics (max. speed 444 kmh, max. ceiling 7000 mt, max. range 4800 km, max. loading 1000 kg or 11 passengers) soon showed its attitude to perform very demanding tasks.

In November 1937, the prototype of this aircraft had completed for Ala Littoria a first experimental no-stop voyage from Rome to Asmara (Eritrea), covering the distance in 16 hours at the excellent average of 380 kmh. In the light of this outstanding exploit, the Experimental Board of the company – under the impulse of lieutenant colonel Attilio Biseo (an esteemed expert pilot, some kind of Air Marshal Italo Balbo for the Italian aviation) and first lieutenant Bruno Mussolini (son of Benito Mussolini and brave pilot himself) – had decided to modify the production version with supplementary fuel tanks, adding radio-transceivers and radio-goniometers and to start up definitely the first Italian transatlantic line.

Such positive were the results that Attilio Biseo decided to set aside the idea (supported by captain engineer Umberto Klinger, chairman of Ala Littoria) of employing for transatlantic flights the new three-engine hydroplane Cant.Z 506 which – between March 20 and 26, 1938 – succeeded in completing an experimental link between Cagliari (Sardinia, Italy) and Rio de Janeiro (Brazil). Biseo’s choice was effectively right and as from February 1939 until the end of 1941, the ‘transatlantic’ SM83 performed several flights across the Atlantic ocean, carrying mail or passengers to Brazil and Argentina.

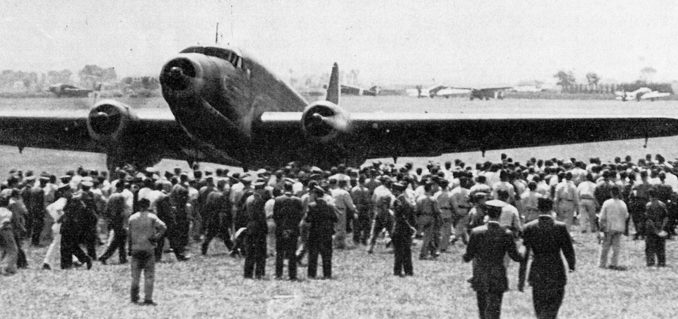

In 1939, more and more attracted by the idea of establishing a similar regular service between Italy and IEA, Bruno Mussolini (in the meantime appointed general manager of LATI) and his staff carried out a long technical cruise with their SM83-ATTE to Tripoli and the Kufra Oasis (Libya), Asmara, Massaua, Gura and Agordat (Eritrea). The voyage proved to be very useful to acknowledge those flight experiences necessary for the future war missions. On June 15, 1940 – only five days after the Italian declaration of war – the SM83 615-1 took off from Guidonia (the air base near Rome) to Asmara, via Benghazi (Cyrenaica, Libya), with six passengers and 100 kilograms of mail onboard, officially starting the ‘special’ air links with the Impero (Empire). Other six flights were completed within the end of June, twelve in July and two in August, carrying on the whole 27 passengers, 406 kg of luggage, 5753 kg of mail and 4047 kg of ammo, medicals and spare parts.

In the same period, a couple of special modified SM79s came to support the eight SM83s of the 615th Squadron, performing – on June 29 – an extraordinary cargo flight to Asmara, carrying almost 1000 kg what with civil and military mail. The same mission was repeated on July 3, 8, 12 and 16, 1940, with the transportation from Benghazi-Berka to Asmara of other quantities of mail, medicals, ammo and some Breda AA 20mm machine guns’ laying devices. The last flight carried out by the SM83s on the Rome-Benghazi-Asmara route was performed on July 20, 1940 by commander Giorgio Carelli. He succeeded in taking to IEA a complete radio station equipment (337 kg) for the Regio Esercito (Royal Army) and about 650 kg of ammo for machine-guns and lubricant oil for airplanes.

On the whole, the operations completed by the SM83s proved to be satisfactory, even if both their limited loading capacity and their scant number forced the Regia Aeronautica’s command at the end of summer 1940 to employ for the links with Ethiopia and Eritrea the more capacious SM75s and SM82s.

The missions of Long Range SM75s

The three-engine Savoia Marchetti SM75 showed – since its very first flight in November 1937 – all the features and potentialities which characterize an heavy multipurpose cargo aircraft, suitable for long range routes and capable to transport huge amounts of cargo or bombs(3). Initially equipped with three Alfa Romeo 126 RC.34 750 hp engines, this aircraft (designed by Alessandro Marchetti) was able to carry 24 passengers on distances of 1500 km, or 18 (equal to 1500 kg of goods) on routes 3400 km long. The SM75 – which was afterwards equipped with three more powerful Alfa Romeo 128 Rc.18 860 hp engines – was 21.60 metres long and weighted at the take off about 1300 kg. The original version of this aircraft could reach the speed of 363 kmh at 4000 mt of altitude and had a maximum ceiling of 6250 mt. Thanks to the setting of special supplementary tanks, the SM75 proved to be able to easily exceed the current range limits, considered prohibitive for any other Italian aircraft (during the summer 1942, the experimental SM75RT flew no-stop from Odessa to Manchuria, for a total of more than 6000 km) and confirming to be the most suitable means to guarantee the links between Italy and IEA.

The first civil SM75s of Ala Littoria were employed on the Rome-Uadi Alfa-Addis Abeba route ever since the beginning of 1939, for a distance to be covered with a two-days-and-a-half long voyage. At the same time other machines were employed for transatlantic experimental flights, supporting the SM83s and one ‘special’ SM79. Still on the eve of the second conflict, the SM75 amazed the technicians from all over the world by completing a few important missions. On January 10, 1939, the SM75I-ITALO piloted by flight lieutenant Giuseppe Bertocco succeeded in transporting a good 10 tons of cargo on a 2000 km distance at the average speed of 330 kmh and – on July 30 of the same year – the same prototype, piloted by captain Angelo Tondi, beat the previous flight length record by flying for 12900 km in 57 hours and 35 minutes.

Those brilliant results, of course, did not pass unnoticed to the chief of staff of Regia Aeronautica, general Francesco Pricolo, who was committed – in view of the imminent war – to the tough task of training his army for the new, dramatic events next to come.

At the beginning of hostilities, being not yet available sufficient quantities of SM82 units (these were the heavy cargoes built in place of the old SM73s), Pricolo decided to immediately employ – for the links to Aegean Sea, Libya and Ethiopia – eleven out of the 34 SM75s in service to Ala Littoria, assigning them to the 147th Transport Group. On June 30, 1940, the SM75 601-6 under the command of captain Umberto Klinger flew from Rome to Asmara via Benghazi, carrying about 1100 kg of mail, medicals and ammunitions. Only ten days later, on July 9, the aircraft was destroyed in the Eritrean airport of Gura, during a sudden English air bombing.

At the beginning of 1941 – after a few months’ operating schedule was carried out to support the Italian troops in Libya, Albania and Dodecanese – an entire section of SM75s was again brought onto the Benghazi-Gura and Benghazi-Gondar (respectively 2700 and 2800 km long) routes and onto the even harder Benghazi-Addis Abeba and Benghazi-Gimma (respectively 3200 and 3300 km) lines. Given the huge distance between the Libyan airports and these latter destination, it soon stood to reason that it was not possible to transport heavy cargoes. This problem led the Italian pilots and engineers to think up emergency solutions to reduce the fuel consumption as much as possible.

Starting from January 1941, all the machines were unburdened at most, equipped with supplementary tanks and compelled to keep low average speed, with an obvious consequent increase of risk to be intercepted by the British fighters dislocated all over Sudan. The British conquest of Cyrenaica and Benghazi (which will remain into English hands from February 6 to April 4) made the links between Italy and its isolated dominions even worse. The temporary unavailability of the strategic Benghazi’s airport forced in fact the Regia Aeronautica’s command to make use of Libyan emergency landing-grounds and to reduce considerably the missions of the aircrafts (SM83, SM75 and SM82) employed in the supply operations to the IEA strongholds. Afterwards, notwithstanding the improvement of the military situation in Cyrenaica (re-conquered by the Italian-German army of general Erwin Rommel), the Italian high command soon realized that on the other hand the conditions of the Duke of Aosta’s army had progressively worsened to the point that any supply of provisions was to be considered useless. Nevertheless, from June to November 1941, the SM75 guaranteed ten more extraordinary links, almost all in support of the Gondar’s stronghold, as Gimma had fallen on June 21. The SM75s (first of which was the I-LUNO) employed in these last missions were equipped with autopilot devices and new tanks, which brought to a good 17000 kg the maximum weight of the aircrafts at the take-off. On June 4, 1941, the SM75 I-LUNO of captain Leonardo Bonzi took off – loaded with medicals and mail – from Benghazi to Gimma but – due to an anomalous fuel consumption of 7000 litres (just the quantity necessary for the flight back) – once reached the destination it could not load the 1000 kg of platinum and mail addressed to Italy. Bonzi was forced to head to Jeddah (Saudi Arabia), where – after a quick fuel supply – he took again the route to Libya and reached Agedabya (Cyrenaica). On July 30, the I-LUNO brought again mail, ammo and medicals to Gondar. After that the aircraft switched on to Djibouti (French Somalia) to supply and there it stopped until August 6, due to an engine failure. On August 16, 1941, the French government imposed to Rome’s government the obligation to apply the International Red Cross’ mark on all the Italian aircrafts as an indispensable condition for further fuel supplies in Djibouti. This requirement was claimed by France in order not to incur in English retortions. In the meantime the situation inside the last Italian stronghold of Gondar – defended by general Guglielmo Nasi’s troops – had become hopeless. The garrison was almost without medicals and ammunitions were rapidly running out. The eager pilots of SM75s were therefore asked for a further effort. On September 19, captain Giovanni Balletti’s SM75 – with Red Cross marks – brought to Gondar 1200 kg of provisions and, once it had loaded half a dozen of civil passengers (all women), headed to Djibouti, going back to Libya soon after. On October 6, the usual SM75-LUNO piloted by commander Max Peroli succeeded once more in supplying Gondar. During the operation, the airplane was hit by a Curtiss P40 of the British Royal Air Force, which consequently was shot on his turn by the French anti-aircraft. A few days later, another ‘emergency’ SM75 took off from a Libyan runway and reached Djibouti to rescue Max Peroli and his crew. This was a very risky mission, also because the British P40s were on the alert and had the peremptory order to put a stop to those annoying Italian raids. Nevertheless, commander Giuseppe Orlandini’s SM75 carried out – having fortune on his side – his tough task, coming back to Libya after a 15-hours cruise and going on to Rome with his precious cargo of pilots and technicians, with a six-hours more trip.

At beginning of November 1941, the Regia’s command tried a few more symbolic links to Gondar, to support – at least psychologically – the besieged. On November 9, the SM75 I-LAME took off from Rome under the command of lieutenant Guido Bertolini (the other members of crew were the second pilot lieutenant Fernando Battezzati, the wireless operator, lieutenant Carlo Profumo and the engineer, lieutenant Giacomo Timolina). The aircraft – loaded with about 100 kg of medicals, cigarettes, food and mail – made a stop over in Libya to reach directly Djibouti on November 11 at 8.00 am. The bad weather conditions and the dark had in fact prevented commander Bertolini from landing at once at Gondar. On November 12 at 1.40 am, the SM75 took off again from the Somali airport, heading to the Italian stronghold. After about one hour of navigation, due to a violent storm and bad visibility, the machine crashed on the summits of the Debra Tabor massif. The whole crew perished in the terrible disaster. With this casualty the epic deeds of the SM75 employed in the links to IEA came to an end: a long and difficult operational cycle which, unfortunately, did not prevent shortly after the collapse of the last strip of the Italian empire. On November 27, in the Italian manufacture Savoia Marchetti of Vergiate (Lombardy) the engineers were fighting against time, trying to fit a new machine (the SM75 I-LINI) with four 413 litres supplementary fuel tanks and one Salmoiraghi auto-pilot device for night-flight. On the same day, general Guglielmo Nasi’s troops were surrendering after a six-months siege.

The ‘marsupial’ SM82s enter in action.

Since the very beginning of war, the viceroy Duke Amedeo of Aosta, as a commander in chief of the land, sea and air forces on the East-African Empire, began to harass the High Command of Rome with several requests for a range of indispensable provisions such as: sanitary equipment, medicals and spare parts for aircrafts. Moreover, the duke asked marshal Pietro Badoglio to do its utmost to send a reasonable number of bombers and fighters in particular. After the commander in chief of Regia Aeronautica Francesco Pricolo was consulted as to this subject, he soon gathered a team of engineers, giving them the task to solve the difficult problem of transferring from Italy to Ethiopia all the necessary provisions for Amedeo of Aosta.

On one hand, the multi-engine bombers Savoia Marchetti SM79 could have been transferred by air in a relatively simple way; on the other hand, the supply of fighters – due to their insufficient range – was apparently impossible. The SM79s, with their average fuel range of about 2000 km, could in fact easily cover the distance between the airports of Cyrenaica and the bases in the north of Eritrea and Ethiopia. The Fiat CR42 fighters had on the contrary only a 1000 km range. Since June 10 until November 14, 1940, a good twenty-three SM79s reached – without any loss – the East African strips, making use of the Sahara oasis of Kufra and Auenat. At the end of December, following to the English conquest of these territories, all the transfers were temporarily cancelled to let the engineers of Marchetti fit a new SM79 series with an enhanced range (to more than 2700 km). Thanks to this expedient, sixteen more modified SM79s succeeded in reaching Ethiopia within February 3, 1941. It was nevertheless the last desperate attempt to provide the worn out aviation of Amedeo of Aosta. During winter 1940-41 the British land and air offensives were going on without interruption, and in March 1941 the Italian stronghold of Cheren was close to the final collapse: these two reasons prevented Rome from further sending of bombers. On March 17, the last SM79 coming from Libya landed in Gondar. But as to the fighters requested by Amedeo of Aosta – for the purpose of checking the continuous raids of English, South-African and French bombers – the Marchetti’s engineers themselves thought up the most original and fit solution. Since the fuselages of the new SM82 ‘marsupial’ cargoes were wide enough, they thought to load on board of them a few Fiat CR42s duly dismounted. After they carried out some successful links, with quite substantial but routine cargoes on board, along the Rome-Benghazi-Asmara route – note that on July 27, 31 and August 1 four SM82s equipped with two supplementary 1300 litres fuel tanks and one 200 litres for luboil, succeeded in reaching Eritrea with more than 1500 km each of standard cargo– the Italian aeronautical command deemed it was the right moment to start up the first transfer operation of a CR42 fighter to Ethiopia with the ‘marsupials’(4).

An SM82 (namely the 608-7) was duly modified to receive on board the Fiat CR42, which was loaded longitudinally through a wide ventral hatch, with dismounted wings and propeller placed along the internal sides of the fuselage.

The whole operation, which took many hours of work to the engineers and technicians, was successfully completed and on August 23 the SM82 608-7 of 149th Group took off, under the command of sergeant pilot Paolo Bonsignore, from Rome heading to Gura (Erithrea) with its special 2100 kg cargo. This successful mission started up a series of a good 51 expeditions, as many as the number of CR42s which the ‘marsupial’ SM82s succeeded in transferring to Eastern Africa in the period elapsed between August 23, 1940 and March, 28, 1941 (only in March the consigned CR42s were 15). Apart from the CR42s, the huge SM82s completed tens of other cargo routine missions, not even easy, flying over hostile territories, well-patrolled by the enemy, during a cycle which, inevitably, led to many losses. The first SM82 which was destroyed was piloted by first lieutenant Pietro Caggiano (the SM82 608-2), who was forced on August 3 to an emergency landing near Tessenei (Eritrea), due to the Handley Page flaps’ failure. The aircraft did a belly-landing while it was taking off, causing such damages to be considered definitely unrecoverable. Afterwards, the technicians of the small airport of Tessenei, dismantled the aircraft bit by bit, getting precious spare parts for the other three engine airplanes on arrival from Libya. A similar episode happened again twenty days after. On August 22, 1940, the SM82 607-6 of first lieutenants Carlo Pivetti and Guido Fraracci was just to come back to Libya from a previous mission when nearly disintegrated in flight due to the explosion of the right engine. Pivetti managed to keep the control and made an emergency landing near Zula (Eritrea). This manoeuvre saved the crew but not the machine. On November 8, first lieutenant Luigi Micheli’s SM82 609-8, while it was coming back from Zula, even had a breakdown of all the three engines, forcing the pilots to ditch in the Red Sea, not far from Massaua. On February 6, 1941, another SM82, stationed in Benghazi due to damage, was set on fire by the crew themselves in order not to leave it in the hands of the British forces coming close. On February 12, the SM82 609-9, after the take-off in Castel Benito (Libya), collided against the high voltage cables of a power plant, crashing to the ground and causing the death of all the crew. One day later, at Zula’s airport, three British Hurricane fighters discerned another SM82 while it was taking off, crashing it to the ground with all its cargo for Gondar. On February 22, lieutenant Armando Ulivi’s SM82 607-9 coming from Libya, was forced to ditch off Zula because of a propeller failure.

If we consider to sum to these losses all the others occurred, due to the obvious withdrawing of the more war-weary means, we have to admit that the results achieved from July 1940 to the end of March 1941 by the only twenty-one SM82s of 149th Group have been definitely amazing. These few aircrafts, commanded by a handful of skilled and brave pilots, succeeded in carrying out successfully more than 280 out of 330 voyages there and back to supply the isolated strongholds in IEA, delivering to their destination a good 51 Fiat CR42 fighters and more than 220 tons of urgent cargoes. A diligence which, even though it was carried out by men and machines at their utmost, could not even modify the fate of the Duke of Aosta’s armed forces.

Notes.

1 It has been calculated that the land, sea and air forces in IEA could count on 8/10 months as to food rationing, 6/7 months for fuel and lubricants, 4 months for coal, 12 months for ammo, 2 months for medicals and 2 months for tires.

2 At the end of summer 1940, the Japanese cargo ship Jamayuri Maru called at Mogadiscio (Somalia) from Japan and discharged about 800 tons of fuel, 200 tons of lubs, about 1000 tons of rice and some thousands of tires, which happened to be unusable (!) as they were wrong-sized for the Italian trucks.

3On May 23, 1943, two ‘special’ SM75s, fit for the loading of 100 kg of bombs each, took off from Rhodes (Greece) for a long and difficult bombing mission on the Eritrean airport of Gura, which had been converted by the Americans into one of the most strategic and efficient repair centres for the US four-engine Boeing B24 employed in Southern Europe and on Port Sudan’s harbour. The two aircrafts, piloted by lieutenants Alberto Villa and commander Max Peroli, took off overloaded with a good 23000 kg (including 11000 litres of fuel necessary for the about 4000 km trip) and completed successfully the mission by hitting ten hangars full of US aircrafts in Gura and half a dozen piers in Port Sudan.

4 The SM82 was designed by Alessandro Marchetti to substitute the old SM73. It was equipped with three Alfa Romeo 128RC.18 860 hp engines and had a maximum load of 4000 kg on a 1780 km distance, but with lesser cargo (1000 kg) the machine could reach a 4000 km distance. The length was 22.90 mt and it weighted 17.867 kg at the take-off. The maximum speed of this three-engine was 344 kmh at 3000 mt of altitude, with a maximum ceiling of 6500 mt. Its first flight was on October 30, 1939 under the control of test pilot Alessandro Passalava. On February 5, 1940, the engineers of Marchetti baptized the first SM82 heavy bomber prototype. This machine – pretty equal to the cargo unit as to its structure – had some peculiarities. A laying device for the release of bombs stored in the mid part of the nacelle (normally 20 units of 100 kg each or 8 of 250kg) was fitted bottom fore the fuselage. A Safat Breda 12.7 mm machine-gun was fit dorsally, and other two Breda 7.7 mm were mounted by the sides of the fuselage. Usually it was crewed by 5 men, instead of the four of the cargo version.

During the second conflict, the SM82s bombers carried out several missions, most of which long range ones. Amongst the targets hit by those huge and robust three-engines, let us mention Gibraltar, Alexandria of Egypt, Suez, Port Said and the refineries of Manama (Bahrain Isles) in the Persian Gulf.

Bibliography.

- The Abyssinian Campaigns. The Official Story of the Conquest of Italian East Africa. Issued for the War Office by the Ministry of Information, London 1942.

- Africa Orientale, Scacchiere Nord, by Federico Cargnelutti, Ed. Del Bianco, Udine 1962.

- Gli Italiani in Africa Orientale, la caduta dell’impero, by Angelo Del Boca, Editori Laterza, Bari 1982.

- La fine dell’Impero, by Alberto Bongiovanni, Mursia, Milano 1974.

- La Guerra in Africa Orientale, Ministero della Difesa, Stato Maggiore dell’Esercito, Ufficio Storico, Roma 1971.

- Vita eroica di Amedeo duca d’Aosta, by Amedeo Tosti, Mondadori, Milano 1952.

- Guerra senza speranza, Galla e Sidama (1940-41), by Pietro Gazzera, Tipografia Regionale, Roma 1952.

- L’Aeronautica nella II guerra mondiale, by Giuseppe Santoro, Esse, Milano-Roma 1957.

- La Guerra Aerea in Africa Orientale, by Corrado Ricci-Christopher F.Shores, Ufficio Storico, Stato Maggiore Aeronautica, Roma 1979.

- ASMAI/III, Archivio segreto, II guerra mondiale, pacco IV, f. 294.

- Dimensione Cielo – Trasporti, Vol. 7 – Aerei italiani nella II guerra mondiale, Edizioni Bizzarri, Roma 1974.

- Come abbiamo perduto la guerra in Africa, di Pietro Maravigna, Tosi, Roma 1949.

Lascia un commento

Devi essere connesso per inviare un commento.